Professor Toby James recommends solutions to the voter identification debate in the UK

Elections and COVID-19: Health and safety in polling stations

BY: Erik Asplund, Lars Heuver, Fakiha Ahmed, Bor Stevense, Sulemana Umar, Toby James and Alistair Clark

Originally Published 02/05/2021 in the International IDEA Blog

Image credit: Republic of Korea National Election Commission

At the start of the pandemic, many countries postponed elections. From June 2020, the trend shifted to holding elections. Thanks to information sharing and peer-to-peer exchanges, election authorities gained an understanding of the risks and prevention/mitigation measures. To date, more than 100 countries and territories have held national or subnational elections that were either on schedule or initially postponed with health and safety measures. But what measures have been introduced so far? What measures have been adopted by countries that have held elections? Are the measures respected by stakeholders? Was voting safe?

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

This article helps to address these questions by presenting information on the health and safety measures introduced into polling stations around the world in 2020. Data was collected from electoral management bodies (EMBs), state institutions, media, and election observation reports from 52 national elections (in 51 countries) in 2020 on how in-person voting was implemented. This was the vast majority of the countries that held national elections but which also had cases of COVID-19 at the time. This analysis forms part of a series that has covered campaign limitations and will cover other parts of the electoral cycle, including special voting arrangements and international elections observation. It forms part of an ongoing study between International IDEA and the Electoral Integrity Project on COVID-19 and elections.

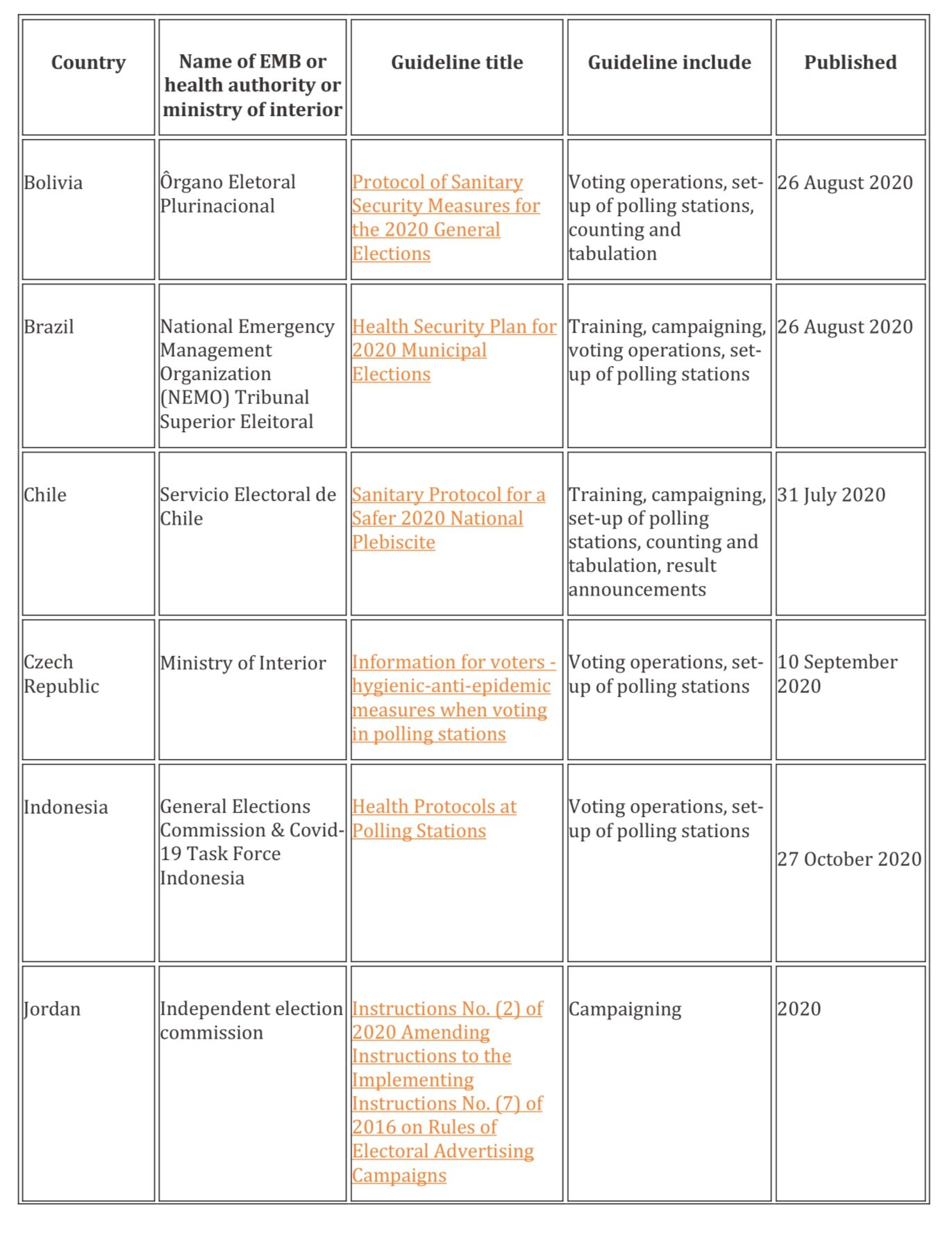

Health and safety guidelines

One of the first steps that EMBs or state institutions took to limit infection risk, often in collaboration with health ministries, was to introduce health and safety guidelines for the election (See Table 1). The guidelines typically focused on the voting operations or the entire electoral cycle (nomination processes, training, voter registration, campaigning, voting operations, set-up of polling stations, counting and tabulation, result announcements). Out of this sample of 20 sets of national guidelines from 19 different countries, 1 covered nomination processes, 6 training, 3 voter registration, 7 campaigning, 18 voting operations, 18 set-up of polling stations, 11 counting and tabulation, and 1 addressed result announcements.

Table 1. COVID-19 health and safety guidelines by country

Source: Authors, constructed using EMB and country information.

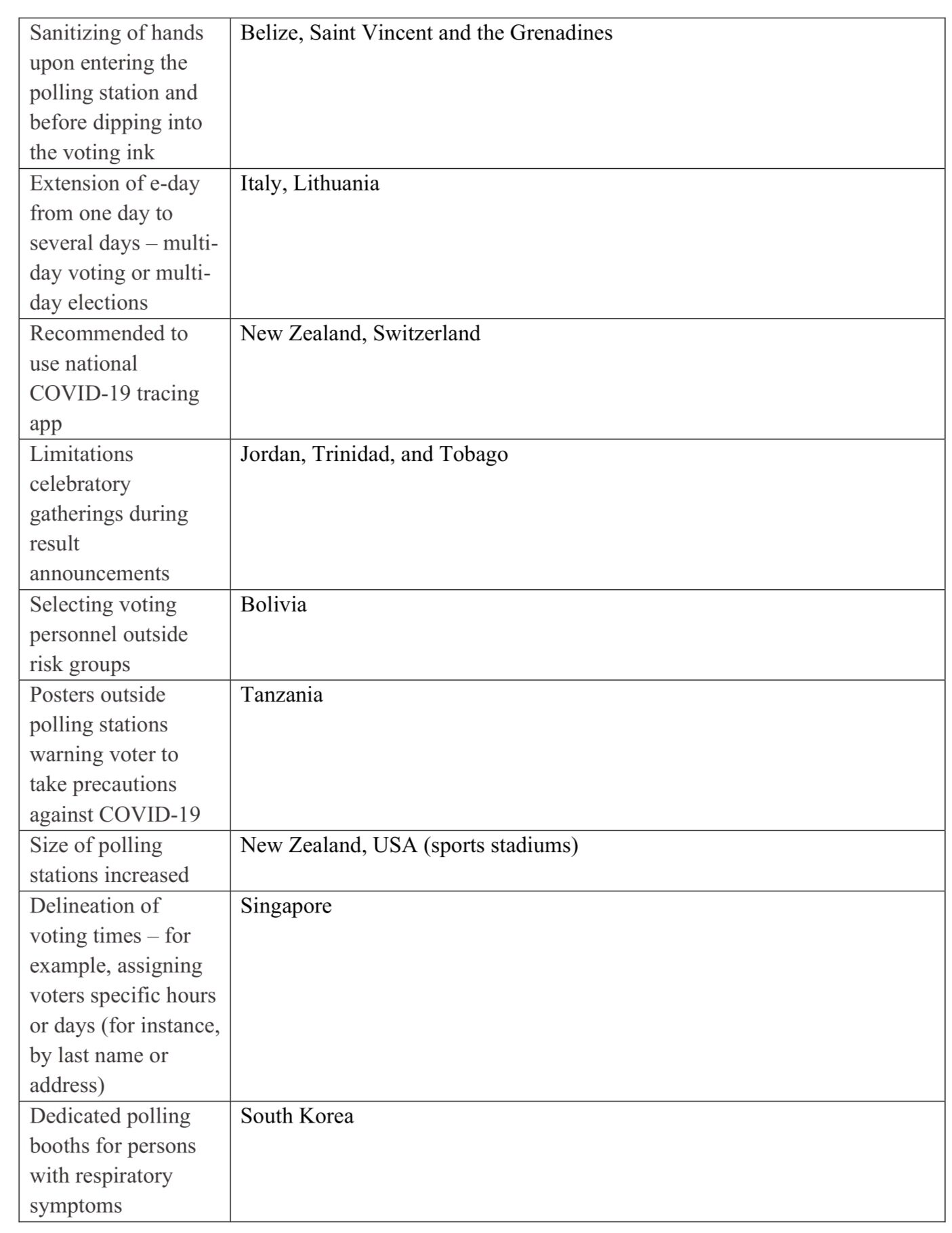

Health and safety measures in polling stations

Health and safety measures for polling stations typically included rules on social distancing, the use of handwashing facilities (or hand sanitizers and disinfectants), ventilation of the polling station, the cleaning of voting materials, and personal protective equipment for polling officials. Almost all countries that have held national elections in 2020 have adopted combinations of these measures (see Table 2).

Beyond these general measures, many countries introduced innovative and extraordinary measures to decrease infection risk. These measures are country and election specific, which may have been exacerbated by spikes in coronavirus. In Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Trinidad and Tobago, the EMBs organized mock polling stations to simulate election day and see whether the new practices would work. In Ghana and Malawi, "COVID-19 ambassadors" were tasked to manage compliance with voters' safety measures. In Jordan and Venezuela, the military took on this role. In Belize, Bolivia, Chile, Italy, Poland, and Singapore, priority queues were in place. Elderly, pregnant women and other vulnerable people could skip the lines at polling stations. For the Bolivian Presidential election, the voter rolls were divided into two-time slots for voting between 08:00-12:30 and 12:30-17:00 to prevent clustering. Commercial activities were also restricted within 100 meters of polling stations, and voting personnel were selected outside the risk groups (between the ages of 18 to 50). In Romania, upon arrival, the elector's temperature was measured at the polling station entrance, and the maximum number of persons at the same time at a polling station was set at a maximum of 15. At the entry and exit, voters had to disinfect their hands. Pens were provided at the polling stations. In Switzerland, besides adhering to the standard COVID-19 mitigating protocols, people were also encouraged to use the Swiss COVID-19 App. The App's purpose is to help stop COVID-19 from further spreading and to detect early possible second wave and tackle it effectively through contact tracing. As of 23 September, it has been downloaded over 2 million times.

Were measures respected?

Based on a review of 31 Electoral Observer Mission’s (EOMs) reports from various missions in 2020, 13 reports on Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Montenegro, Myanmar, Niger, Serbia, Seychelles, and Tanzania suggest that restrictions were often not consistently respected and poorly enforced. In general, EOMs stated that compliance to health and safety measured in place varied inside polling stations, and enforcing restrictions outside polling stations was difficult most of the time. The use of masks and disinfectant was followed in most cases. Adherence to social distancing rules turned out to be to most challenging in many cases due to polling stations not being spacious enough for regulations to be adhered to.

Table 2. Health and safety measures introduced during the 2020 national elections to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Source: Authors, constructed using International IDEA, media reports, and EMB data. Note: This table is based on 51 countries that held 52 direct national elections and referendums from 21 February until 31 December 2020. All of the countries included in the table had one or more confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection. The table does not cover health and safety measures introduced during national by-elections or subnational elections.

Was in-person voting safe?

Have all these reforms helped to protect public health? To date there have been very few reports linking voting arrangements with community transmission. However, some studies have been carried out and are at times contradictory. For example, in one study, focusing on the Wisconsin, USA, primary election showed “statistically and economically significant association between in-person voting density and the spread of COVID-19 two to three weeks after the election” whereas another study focusing on the City of Milwaukee from the Wisconsin CDC found no clear increase in cases, hospitalizations, or deaths. Beyond the US, health authorities in South Korea concluded that no local transmission occurred from the Parliamentary election held in April 2020, and a scientific article published in August substantiated this claim. In contrast, a French study on municipal elections in March 2020 suggested an increase in numbers of hospitalizations due to the polls, but mainly in areas already showing high transmission levels. However, they found that the election did not contribute to virus transmission in areas with already low levels of COVID-19.

There needs to be caution in interpreting this evidence. Without a consistent and robust estimation methodology which can link voting arrangements directly as a cause of transmission to individual voters, separate to ordinary community transmission, it is difficult to know when and where the virus was in fact caught. Variations in data availability between countries, and different methods and approaches among studies, make it very difficult to come to general conclusions. Media reports could also be less reliable in this respect; focusing on the anecdotal rather than aggregate picture-and may have the potential to spread misinformation. Nonetheless, Votebeat, a nonpartisan reporting project, provides some anecdotal evidence that many US poll workers tested positive during the November 2020 Presidential election.

Conclusion

Although risks remain, it appears that countries are more willing to hold elections because of an improved understanding of the virus. Time has also elapsed since the pandemic started, which has enabled lesson drawing from overseas, risk management plans to be adapted, and election planning to take place. Health and safety measures will clearly require further investment in elections to protect the safety of staff, campaigners, and votes. They will also be needed to assure citizens that voting is safe—so that turnout is not affected. The early publication of guidelines will help them to be implemented—and mechanisms for enforcement need to be considered by policy makers too.

Main findings on health and safety measures in polling stations

Health and safety measures have been adopted by almost all countries running elections and were similar across countries.

Some countries have adopted more safety measures than others.

Compliance to health and safety measures varied inside polling stations, outside was difficult to enforce. Problems related mostly to space so that social distancing could be adhered to (rarely respected or possible)

The use of masks and disinfectants seems to be in place and broadly respected inside polling stations in most countries.

Further investment will be required in health and safety mechanisms for elections to ensure health and safety, but also to prevent voter turnout declines.

About the Author

Erik Asplund is a Programme Officer in the Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA. He is currently managing the Global Overview of COVID-19: Impact on Elections project. Other focus areas include Electoral Risk Management, Financing of Elections and Training in Electoral Administration with an emphasis on BRIDGE and Electoral Training Facilities.

Lars Heuver is a graduate student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Uppsala University, currently doing an internship at International IDEA. Fakiha Ahmed is a Master's student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Uppsala University and is currently doing her internship at International IDEA. Bor Stevense is a second-year Masters student at the University of Uppsala for the Peace and Conflict Studies programme, currently doing an internship at International IDEA. Sulemana Umar is a second-year Masters's student at Lund University pursuing International Development and Management Programme. He is currently an intern at International IDEA. Toby S. James is Professor of Politics and Public Policy in the School of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies at the University of East Anglia. His most recent books are Comparative Electoral Management (Routledge, 2020) and Building Inclusive Elections (Routledge, 2020). He is co-convenor of the Electoral Management Network. Alistair Clark is Reader in Politics at Newcastle University. He has written widely on electoral integrity and administration, electoral and party politics. He is the author of Political Parties in the UK, 2e (Palgrave 2018). He tweets at @ClarkAlistairJ.

Lars Heuver, Fakiha Ahmed, Bor Stevense, Sulemana Umar, Toby James and Alistair Clark

Elections and COVID-19: How election campaigns took place in 2020

BY: Erik Asplund, Lars Heuver, Fakiha Ahmed, Bor Stevense, Sulemana Umar, Toby James and Alistair Clark

Originally Published 02/02/2021 in the International IDEA Blog

Image credit: Andrew Keymaster on Unsplash

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed a profound strain on electoral democracy worldwide. Many elections have been postponed, while others have been held with adaptation.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

One key aspect of the democratic process that has been thought to be affected by the pandemic is electoral campaigning. Campaigns are opportunities for political parties and candidates to spread their ideas about how public policies should change—or remain the same—in the future. Campaigns allow public conversations and deliberation about the future of the country. They allow citizens to weigh up their options when they arrive at the ballot box in a more informed way. Campaigns also play a critical performative role in democracy. They are rituals that signal that the democratic process is underway.

But there is also the risk that campaigns could involve not just the spreading of ideas—but the COVID-19 virus. There have therefore been prominent and ongoing debates about whether the campaign should be restricted to protect public health. Which countries have introduced such restrictions? What alternative forms of campaigning have been adopted? Do campaigns really spread the virus, or is this a convenient opportunity for incumbent governments to clampdown on political activity?

This article helps to address these questions by presenting information on political campaigns around the world in 2020. Data was collected from media and election observation reports from 52 national elections (in 51 countries) in 2020 on how the campaigns operated. This was the vast majority of the countries that held national elections and which also had cases of COVID-19 at the time. This analysis forms part of a series that will cover other parts of the electoral cycle, including health and safety arrangements in polling stations, special voting arrangements; and, international election observation. It forms part of an ongoing study between International IDEA and the Electoral Integrity Project on COVID-19 and elections.

Limitations to traditional campaigning

Roughly half of the countries studied saw limitations on traditional campaigning because of government restrictions on movement and public gatherings. Restrictions included limits on the number of participants allowed to attend public gatherings and complete bans on political rallies or events. In total, 22 of out 51 countries (43 per cent) saw COVID-19 restrictions that limited some freedom of association and assembly during election periods (See Table 1).

For example, ahead of the July 2020 Parliamentary elections, Singapore banned public gatherings effectively by not granting permits for election meetings, including rallies and gatherings at assembly centers. Access to nomination centers was also restricted. In Montenegro, public gatherings were limited to 100 people, and rallies were banned ahead of the August 2020 Parliamentary elections. In Jamaica, ahead of the August 2020 General election, political motorcades were not allowed, meetings were limited to 20 people, and canvassing was restricted to five people per group. In Jordan, gatherings were limited to 20 people, and rallies were banned ahead of the November 2020 General election. Furthermore, candidates and supporters were expected to refrain from any party celebrations and respect a four-day nationwide curfew directly after the vote.

Door to door campaigning was often still allowed. In Singapore this could take place, but with no more than five people per group. Each group was also required to keep a1m distance from other groups, should wear masks, needed to keep their interactions brief and avoid shaking hands. A restriction of five persons per campaign group was also in place in Jamaica.

Other health measures that have been introduced include temperature checks for campaign events (Myanmar), sanitation of indoor venues (Chile), a maximum time duration during gatherings (Sri Lanka), as well as dedicated or sanitized microphones (Myanmar, Sri Lanka), among others.

Were restrictions observed?

Restrictions may have formally been put in place, but Election Observation and media reports have noticed that large scale in-person rallies have sometimes gone ahead despite government limits. In Myanmar, the limit of 50 people who could be present at a rally were not complied with, nor enforced by the authorities. Also according to ANFREL, guidelines on social distancing and usage of face masks was not respected during campaign activities. In Moldova, restrictions allowed no more than 50 people to join public events, something that was not always respected by several candidates. The OSCE/ODIHR report about the elections in Poland said that just before the second round, political campaigns organized many direct meetings with voters that attracted large gatherings, during which COVID-19 restrictions were not respected and poorly enforced. The Citizens Engagement Platform Seychelles (Ceps) noted that health regulations were not entirely appreciated by candidates and activists during the campaigns. Moreover, in Malawi, mass campaign rallies leading up to the presidential election were reported despite that gathering was restricted to 100 people.

The move to remote campaigns

With these restrictions in place, many political parties and candidates did, however, campaign through social media and other online platforms to get their policy options to resonate with prospective voters. Indeed, the pandemic may have helped accelerate a shift in campaigning in this direction. In Singapore, parties discussed their plans through e-rallies on Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and TV and radio. In Kuwait, social media was used extensively, particularly Twitter, Zoom, and WhatsApp, as in-person meetings at 'diwaniyas' (party reception areas) were banned. In the USA, ahead of the November 2020 Presidential election, both the republican and democratic parties made use of social media and even held party conventions online before adopting non-traditional rallies such as drive-in events and those held at airports.

Non-digital mechanisms have also been used during the pandemic by parties and candidates to convey their message, especially in countries where there is a lack of sustainable internet penetration. Examples include short-message service (Mali), telemarketing (USA), postal mailings (Serbia), and TV, newspapers, and radio talks show and political advertising (Chile, South Africa, Dominican Republic, Poland, Seychelles, among others). Some of these—such as TV, newspapers and radio shows—are likely to be a continuation of pre-existing campaign practices.

Are campaign events safe?

Have all these reforms been necessary to protect public health? Or are they disproportionate restrictions on political freedoms? There have been some reports claiming that coronavirus spread because of elections held in 2020. There needs to be caution in taking this evidence as-read. Without a robust methodology which can link campaign events directly to transmission separate to ordinary community transmission, it is difficult to know when and where the virus was in fact caught. Media reports could also be less reliable in this respect, focusing on the anecdotal rather than aggregate picture—and may be more likely to spread misinformation. Nonetheless, the reports provide some useful anecdotal information suggesting campaign events can be sources of transmission. For example, exceptions from one study suggested that 30,000 people were infected and expected that around 700 would die of COVID-19 due to the 18 outdoor rallies organized by the Trump campaign. In Burkina Faso, according to a local newspaper, the large gathering during the electoral campaigns could also be attributed to an increase in coronavirus cases.

Exceptions at the subnational level include Malaysia's Sabah state election, where instructions for campaigning during the pandemic from the Electoral Commission were not adhered to during campaigns. After the elections, the Prime Minister conceded that the recent spike in COVID-19 could be attributed to the political campaigns. Ten politicians and three election officials tested positive for coronavirus after the elections. According to media reports, 20 candidates contesting in the November 2020 Brazil Municipal elections died of COVID-19. In France, both Le Figaro and France Télévisions reported stories about the election and the further spread of coronavirus. Some candidates and polling officials had either shown symptoms, been diagnosed as having the virus, or passed away shortly after the election due to the virus. While it is difficult to know the exact total number of candidates who stood for election in each of these elections, it is likely to have been in the thousands in each country.

The balancing act between public health protection and democratic discussion and contestation is, therefore, an important one. Some adaptation of the electoral process is clearly needed to preserve human life given the known risks. However, freedom of expression is crucial to campaigning and the ability of ideas and information to flow during the electoral process should be restricted as minimally as possible. Given that different aspects of the electoral campaign has a different focus in different countries—bespoke rather than ‘one sizes fits all’ approaches will probably be needed.

Table 1. Limits or bans on traditional campaigning ahead of elections in 2020 by country

Limit on number of participants at public gatherings:

Burkina Faso (50), Croatia (10 indoors), Guinea (100 for 18 October 2020 election), Iceland (100), Jamaica (20), Jordan (20), Malawi (100), Mali (50), Moldova (50), Montenegro (50 indoors and 100 outdoors), Myanmar (50), North Macedonia (1,000), Poland (50-150), Romania (20 indoors, and 50 outdoors), Serbia (50-500), Sri Lanka (100), USA (depending on the state)

Political rallies or events banned:

Croatia (ban on holding public events and large gatherings), Dominican Republic (rallies banned), Iran (candidates barred from campaigning on the streets), Jamaica (motorcades banned), Jordan (banned election rallies), Kuwait (rallies banned), Montenegro (public gatherings and rallies banned), Poland (public gatherings were officially prohibited) Serbia (Campaign suspended), Singapore (rallies banned), Seychelles (rallies banned), USA (depending on the state)

No information found on campaign limitations or bans:

Algeria, Belarus, Belize, Bermuda, Bolivia, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chile, Cote d'Ivoire, Czech Republic, Egypt, Ghana, Georgia, Guinea (22 March 2020), Israel, Italy, Kyrgyzstan, Liberia, Lithuania, Mongolia, New Zealand, Niger, Russia, Tanzania, South Korea, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Syria, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela.

(Source: Authors, constructed using International IDEA, EOM and media reports and EMB and country data.)

Note: Countries included more than once in the table had both limitations and bans on rallies during different periods. This table is based on a dataset of 51 countries that held 52 direct national elections and referendums during the period 21 February until 31 December 2020. All of the countries included in the dataset had one or more confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection. The dataset does not cover national by-elections.

Main findings on campaigns

Many governments are limiting traditional campaigning as part of broader COVID-19 measures. Typically, by banning or reducing the number of people who can attend campaign events.

Some observations and media reports find that campaign limitations and health and safety measures are not being respected or enforced.

Many EMBs, in collaboration with health ministries, introduced health and safety guidelines for political parties, candidates, and supporters.

There are some anecdotal country reports that campaigns have led to increased cases of COVID-19 and deaths, although these need to be treated carefully.

Remote campaigning has increased in many countries as a result of the restrictions, especially on social media.

About the Author

Erik Asplund is a Programme Officer in the Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA. He is currently managing the Global Overview of COVID-19: Impact on Elections project. Other focus areas include Electoral Risk Management, Financing of Elections and Training in Electoral Administration with an emphasis on BRIDGE and Electoral Training Facilities.

Lars Heuver is a graduate student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Uppsala University, currently doing an internship at International IDEA. Fakiha Ahmed is a Master's student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Uppsala University and is currently doing her internship at International IDEA. Bor Stevense is a second-year Masters student at the University of Uppsala for the Peace and Conflict Studies programme, currently doing an internship at International IDEA. Sulemana Umar is a second-year Masters's student at Lund University pursuing International Development and Management Programme. He is currently an intern at International IDEA. Toby S. James is Professor of Politics and Public Policy in the School of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies at the University of East Anglia. His most recent books are Comparative Electoral Management (Routledge, 2020) and Building Inclusive Elections (Routledge, 2020). He is co-convenor of the Electoral Management Network. Alistair Clark is Reader in Politics at Newcastle University. He has written widely on electoral integrity and administration, electoral and party politics. He is the author of Political Parties in the UK, 2e (Palgrave 2018). He tweets at @ClarkAlistairJ.

Lars Heuver, Fakiha Ahmed, Bor Stevense, Sulemana Umar, Toby James and Alistair Clark

Wales is giving 16-year-olds the vote – but they may have to wait a little longer

Toby S. James considers how elections in Wales are being adapted to the pandemic.

The scene was set for May 6 2021 to be a historic day for democracy in Wales. It would be the first time that 16 and 17 year olds would be able to vote in an election in UK history.

It still might be. Although the pandemic has forced the country into lockdowns, the Welsh government says it is committed to the elections going ahead. The Senedd has passed legislation that would enable voting over several days, with safety in mind. However, that same legislation also makes it possible to delay the vote for up to six months.

Although we naturally should always want elections to be held, there are strong arguments for delaying the polls this time. Holding the election will bring together millions of people. Roughly 625,000 people entered a polling station at the last Senedd election in May 2016 (a further 395,878 voted by post). Add to this the thousands of poll workers, presiding officers, counting officers, let alone campaigners outside the polling stations, or a family member hanging around outside to hold the dog, and you have a lot of people coming together. Coronavirus spreads quickly.

Should the advice be from the Medical Office of Wales that a delay is necessary to protect human life, then democracy will have to wait a little while. Election postponements are not always power grabs. There have indeed been many delays around the world during the pandemic, with elections in at least 75 countries being postponed in the last year. Most of these were reorganised relatively quickly.

It’s also harder to hold a high-quality election in a pandemic. Some groups, candidates or parties may be left at a disadvantage. There have already been claims that bans on leafleting are unfair to small parties. Experience from Europe showed that lockdowns prevented the opposition campaigning in Poland, giving the incumbent president, who still regularly appeared on TV, an advantage.

There is also a danger that people, especially those at higher risk, may be put off voting. Voter turnout has been much lower during the pandemic than it otherwise might have been. Most European nations that have held a parliamentary election since the start of the crisis have seen fewer people participate.

Turnout down. Author, using data from International IDEA., Author provided

Although there are many factors that push turnout up and down, there does seem to be a pandemic decline, probably because people are worried about catching the virus at polling stations.

Elections are also simply more difficult to organise in a pandemic. They rely on an army of poll workers who, research shows, are often elderly and retired – and therefore more vulnerable to COVID. Although the vaccine roll-out is making progress, people are likely to think twice about signing up to work on polling day. Schools and parents may also be reluctant to allow school buildings to be used as polling stations.

How the polls can be held

Elections have been held in over 100 countries since the pandemic began. With partners, the Electoral Integrity Project has investigated how many have adapted to changed conditions.

While social distancing measures and hand sanitiser go a long way to improving safety, early voting is a more powerful tool in a government’s kit. That’s because it makes elections safer, with less risk that turnout will decline.

The argument made for going ahead with the May elections in Wales (and the rest of the UK) is often that the US managed to hold a national election in November. American voters, however, made heavy use of postal voting and early voting. Over 65 million people voted through the post, while a further 36 million voted ahead of the day of the election at specially arranged polling stations.

It would be logistically difficult to enable early voting in Wales at this point because of the need to find extra venues to host polling stations. But this is an important step to prevent a decline in turnout – which suggests it might be worth delaying the May vote.

Political parties should work together to try to reach a consensus about how the election should be run, and whether a delay is necessary. Wales, in particular, has done good work to avoid the risk of the Welsh government delaying (or fast tracking) in a way that might maximise its own political advantage. Local elections in England may yet be postponed by the Conservative government acting unilaterally, but in Wales, the Welsh government must first consult with the chief medical officer for Wales and the independent presiding officer of the Senedd. Then, two thirds of the Senedd would have to vote to agree to the date change.

Wales’ election on May 6 might, therefore, be delayed. But if it is, and if early voting procedures are put in place, then the decision would be through consensus and in line with the lessons that the world has learnt about how to run an election in 2020. It can therefore still be a historic day to be proud of.

This blog was first published on The Conversation.

Why Republicans haven’t abandoned Trumpism

Parties can and do change. But these four barriers stand between the Republican Party and moderation.

By Pippa Norris

Feb. 8, 2021 at 7:45 a.m. EST Published in the Washington Post/Monkey Cage

Most congressional Republicans continue to embrace Trumpism, despite some wavering after the deadly Capitol riot. The GOP has backtracked on impeachment, with most Senate Republicans voting against holding an impeachment trial. State parties have punished Republicans such as Rep. Liz Cheney (Wyo.), who spoke and voted in favor of impeachment, rather than members such as Sens. Ted Cruz (Tex.) and Josh Hawley (Mo.), who supported the falsehood that the presidential election had been stolen. House Republicans did not sanction Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (Ga.), despite her past endorsements of wild conspiracy theories.

But the notion that the GOP would suddenly abandon Trumpism once Donald Trump left the White House has the basic story upside down. Trump wasn’t the cause of authoritarian populism; his success was the consequence of deeper underlying forces.

When do parties change?

Median voter theory suggests that there is a normal distribution of views in society, with most people clustered in the midpoint across the ideological spectrum. If so, the shock of major electoral defeats will push rational vote-seeking parties away from the extremes and back toward the political center, where they can harvest the most support. That’s particularly true in electoral systems requiring a majority of votes to win power, as parties realize that they need to broaden their appeal to gain support from moderates and independents. If they do not learn and adapt, if their only appeal is to the extremes, parties will remain in the electoral wilderness.

Under Trump, the GOP lost the House, the Senate and the White House. So unless Republicans don’t understand the true distribution of public opinion, which is always possible, any rational vote-seeking party should recognize the risks of the Trump brand and move the party back toward the conservative center-right.

Right?

Not so fast. Party rebuilding typically takes a long time, a lagged process typically occurring after the shock of a series of major electoral defeats. Four important barriers hinder GOP renewal.

Barrier 1: The Republican Party has adopted authoritarian-populist values

The first problem is that authoritarian-populist values have gone viral and spread deeply through the Republican Party. Expert estimates of political parties’ ideological positions suggest that the party of Lincoln has become willing to undermine democratic principles in pursuit of power, much like the Alternative for Germany, Austria’s Freedom Party and Hungary’s Fidesz. Other independent evidence confirms these estimates.

It’s not just Trump and the top congressional leaders who embrace authoritarian values. This mind-set has penetrated the party nationwide. In December, the Electoral Integrity Project asked 789 experts to estimate the ideological position of U.S. state parties. As you can see in the figure below, some state Republican parties, such as those in Vermont and Hawaii, continue to respect liberal democratic principles. But most, like those in Wisconsin and Nevada, have abandoned these values.

The MAGA base similarly doubts basic democratic principles, such as the integrity of American elections. Even since Joe Biden’s inauguration, about 8 in 10 Republican voters continue to endorse the “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was rigged and Biden’s victory is illegitimate.

Barrier 2: Republicans see diversity as a threat, not an opportunity

One reason so many Republicans are willing to believe that contests are rigged is that the party has gradually lost faith in its capacity to win the White House fair and square by respecting democratic principles, norms and practices. Since 1992, Republicans have not won a majority of the popular vote in seven out of eight presidential elections. Trump lost the popular vote by almost 3 million in 2016 and by 7 million in 2020.

Instead of adapting, Republicans have come to fear the growing ethnic and racial diversity of the American electorate as an existential threat to the party’s survival. When Republicans control the state legislature, instead of moving toward the center-right to expand support, they fiddle with the rules and rig the outcome in their favor. More than 100 new state legislative bills currently seek to restrict voting rights, particularly affecting communities of color.

Barrier 3: Institutional incentives

Moreover, the institutional incentives facing individual Republican lawmakers diverge from the collective interest of the party in seeking to win the White House. The structural rules of the game insulate congressional Republicans from needing to broaden their appeal.

The House (since 2010), the Senate and the electoral college have all been asymmetrical disproportional, meaning that Republicans have a built-in advantage in translating their share of the popular vote into seats. As a result, Republican members of Congress can get elected in White and rural America. But the party has repeatedly been unable to win a majority of the popular vote for the White House with this strategy.

Gerrymandering means that Republicans can also win House seats by appealing to their MAGA base in safe districts. Where parties are deeply polarized, this tendency is reinforced by primaries and caucuses, which typically engage the most partisan voters. Lawmakers fear angering primary voters, even if this means ignoring their district’s general electorate.

Barrier 4: Party cultures are slow to change

Finally, the party’s unwillingness to abandon Trumpism is reinforced by institutional inertia. Congressional Republicans got elected under Trump, so why should they change? It’s risky. Normally, any party must be shocked by successive landslide electoral defeats to oust the old regime. Party renewal grows from subsequent electoral gains, gradually bringing moderate new blood into the party. So far, the reverse has been happening as moderates leave in despair and QAnon acolytes step up. Enough are elected to Congress to block liberal legislation and trigger gridlock.

Parties can and do learn. They can move closer to the median voter. But congressional Republicans haven’t suffered the shock of landslide defeats. Rather, the party has gained House seats, insulated by gerrymandering.

Republicans could abandon authoritarian populism and move back toward the traditional conservative center-right — becoming the party of Mitt Romney (Utah), Susan Collins (Maine) and Lisa Murkowski (Alaska). A minority seeks to do so. But fearing the dedicated MAGA base’s wrath, and hoping that new restrictions on voting rights will help win seats in the 2022 midterm elections, the Trumpist wing in Congress has an incentive to block party renewal.

Pippa Norris

Pippa Norris, the McGuire lecturer in comparative politics at Harvard University, is the founding director of the Electoral Integrity Project and a co-author, with Ronald Inglehart, of “Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism.”Follow

Scotland is ready to run the May elections, despite the pandemic

Important Scottish parliament elections are scheduled for May 2021 and the expectation is that the Scottish National Party will emerge as the biggest party, potentially even with enough votes to form a majority government, after ruling as a minority since 2016.

However, it has been argued by former first minister Henry McLeish, among others that these elections, should be postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said that she sees “no reason at this stage why the election wouldn’t go ahead”. The subtext for critics might be “why would she, with the polls so favourable?” Victory for the SNP would allow it to claim a mandate for a second independence referendum. This is, therefore, a historic political opportunity for the SNP to realise that goal. It could be a defining moment for Scotland and the UK.

Election postponements are deeply political and there is often an incentive for those in power to keep or switch the date for political advantage. But in this case, Sturgeon doesn’t need to be playing politics. The lead in the polls is sizeable and has been consistent – often by more than 30 percentage points. So a delay would be unlikely to make a difference.

Also, Scotland is in good shape to hold these elections. Electoral administrators and policymakers have been planning in depth for COVID-19 mitigations for May’s elections since at least mid-2020.

The Scottish parliament has the power to legislate on electoral law for Scottish parliament and local elections. At the end of December, it passed the Scottish General Election (Coronavirus) Bill. This provides for a range of contingencies to allow the elections to proceed. Crucially, this was passed on a cross-party basis, with 117 votes for and none against. Scotland was also unique among the UK’s four electoral jurisdictions in allowing a few council byelections to be held late in 2020, so Scottish electoral administrators have some experience of conducting elections under COVID-19 circumstances. This situation contrasts with the renewed debate in England, where no such cross-party legislation has yet been developed.

How elections will work

The contingency legislation for the Scottish elections contains various measures to make voting possible within the confines of coronavirus rules.

To minimise traffic at polling stations, for example, more people will be encouraged to vote by post. Pre-pandemic, rates of postal voting had already been on the increase – up from 11.2% in 2007 to 18% in 2016. Levels of postal voting under pandemic conditions are expected to be around 40%, but the legislation makes it possible for the vote to be held entirely by post, if that’s necessary.

Postal voting is logistically complex. It takes time to register voters for it and to implement the various security measures that legislation rightly provides for. The Scottish government is providing extra funding to electoral registration officers to ensure they have the resources to process increased numbers of postal votes. If the vote does have to be fully postal, the elections will need to be postponed for six months.

The legislation allows for additional contingencies should the pandemic worsen. There has been discussion about extending voting over several days to help with social distancing. This was put into place in Queensland, Australia and is often recommended. It would be logistically challenging and may necessitate a delayed election. Provision has been made for this in the Scottish General Election (Coronavirus) Act, allowing ministers to extend voting on the recommendation of the Electoral Management Board. The expectation remains that the election will be held over one day.

Provision has also been made should MSPs need to delay returning to parliament to choose a first minister because of the pandemic. Regardless of any potential postponement, the elections have to be held by November 5 2021.

Making it happen

A widespread public education campaign will be key to ensuring the May 2021 Scottish parliament elections are a success. This should focus on the need to register early for postal votes. Often voters leave this to close to the deadline. Doing so in 2021 could lead to considerable pressure on electoral administrators. It could also lead to voters missing the deadline. This could mean that they have to attend polling stations, increasing the risk of spreading coronavirus. This postal vote campaign needs to start now. It needs to use all available channels of communication.

There needs also to be clear communication to the media, to voters and political parties that counts will take longer. Results are unlikely to be available overnight.

Communicating what to expect in polling stations will also be important. Voters will find social distancing in place, where appropriate, with one-way systems and possible limits on numbers in polling stations. There will be regular sanitisation and an expectation that voters will wear face coverings. In recent years, there has been a conspiracy theory and movement against pencils in polling booths (using #UsePens on social media), suggesting that pencil marks are insecure and might be changed. In 2021, voters may actually have to take their own instead of using a shared pencil, or single-use pens or pencils may have to be provided.

A fine balance will need to be struck on any future decisions if the Scottish pandemic gets worse. Principles of electoral integrity normally suggest that decisions should be made as early as possible to allow voters, parties and administrators time to adapt. The pandemic puts pressure on this principle – and changing conditions may require a last-minute rethink. But as it stands, Scotland has put in much of the preparatory work and appears ready to conduct these crucially important polls as originally scheduled.![]()

Alistair Clark, Reader in Politics, Newcastle University and Toby James, Professor of Politics and Public Policy, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Disclosure statement:

Alistair Clark has received funding from the ESRC, British Academy, Nuffield Foundation and The Leverhulme Trust.

Toby James' research has been externally funded by the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, British Academy, Leverhulme Trust, AHRC, ESRC, Nuffield Foundation, SSHRC and the McDougall Trust.

UK government has delayed elections longer than most countries – and England still isn’t ready to hold pandemic votes in May

Which activities are essential during a pandemic? Across England, school buildings have been closed, as have many shops, businesses and sports facilities. So what about elections? Should they go ahead? It’s an important question since local elections are scheduled to take place in the UK in May.

Among them are the English elections that were originally meant to take place in May 2020 but were postponed because of the pandemic. That means that as well as votes in Scotland and Wales, a bumper set of contests is now scheduled in England for May 2021. There will be votes for English councils, police and crime commissioners, the London mayor, the London Assembly, regional mayors and local mayors.

There has been some speculation that these too might be postponed. When asked, the prime minister has said that we have to “keep it under review”. But keeping things under review isn’t enough. If the English votes are to go ahead, important steps need to be set in motion immediately.

Running an election during a pandemic means making significant changes to the normal routine. Citizens may not want to risk their health and decide not to vote if their safety can’t be assured, so measures need to be taken to ensure their safety.

But many of the English local elections have been postponed once already. At some point, it becomes a question of whether postponing poses a threat to democratic freedoms. Some officials have had an extra year in office as a result of the first delay. These elections matter because they hold politicians to account and allow citizens to shape how public services are run. They will also provide the first litmus test for how the current UK government is performing since the 2019 general election.

2020 elections

Many elections worldwide were postponed in 2020 so England was not alone. Our research with International IDEA shows that between February and December, 75 countries and territories postponed elections for at least a short time. Most were rescheduled very quickly, however.

Italy held a referendum and elections, due in late March, at the height of the first wave, in September. Countries that did not hold or reschedule a postponed election were very troubled political systems such as Somalia. For context, Somalia has not conducted a direct popular vote since 1969.

The UK was unusual in postponing for a whole year. It has already delayed as long as Hong Kong, a postponement that even the Trump administration described as undermining “the democratic processes and freedoms”.

How to host a pandemic election

There have been more than 100 national and local elections that did happen around the world in 2020 and we have found many success stories.

A key takeaway was the importance of enabling postal voting. This facilitates higher turnout and reduces risks to staff and the public. Bavaria showed how elections in which everyone votes by post can be organised with very short notice.

However, it would be difficult to organise all-postal elections for May in England, as administrators have warned. There are rigorous anti-fraud mechanisms in place which would require the electorate to provide their signatures and date of births before being given a postal vote. Only one in five have done so so far.

Only if these mechanisms were relaxed could all-postal elections be feasible for May, which means this isn’t really a serious option. It would, however, be possible with a short delay if everyone could be encouraged to apply for a postal vote since there are no limitations on who can apply.

Urgent measures

There are other best practices that the UK government has been slow to adopt. It needs to act urgently to have them in place.

For a start, voting should be spread over several days. This makes it easier for voters to socially distance in polling stations while giving everyone time to take part. Even local elections, where turnout is low, have peaks and queues during busier moments. Early voting can also encourage higher turnout. There is time for such legislation to be drawn up and introduced. This would improve elections anyway, if the government acts now and is clear about the intentions of such legal changes.

The people running these elections also need more funding so that they can make voting safe. In Australia, polling stations were provided with hand sanitiser and extra staff were laid on so that extra cleaning could be done. In South Korea, temperature checks were taken before citizens entered polling stations. This all took money. The provision of PPE in South Korea was estimated to add $16 million to the cost of running an election in March 2020. Hand sanitiser and other health measures added $32-37 million to the budget for Sri Lankan elections.

Unfortunately, the UK government has not promised additional funds to make the 2021 elections safe. Chloe Smith, the minister for constitution and devolution, apparently envisages no additional funding being made available to local authorities to conduct the 2021 elections. Writing to electoral officials in September, she said only that local authorities had been given £3.7 billion of un-ringfenced funding to deal with coronavirus in general, and that it continued to be local authorities’ responsibility to fund local elections. This is unacceptable. More is needed.

Decision making needs to be open and transparent. We’ve seen examples of authorities holding public hearings about elections during the pandemic. But decisions are being made unrecorded behind closed doors amongst government officials. Groups representing voters with special needs need to be heard in particular so that everyone is included.

COVID-19 is presenting a very changeable situation and the new strain in the UK may cause plans to change. But if the May elections are to go ahead in England, urgent and decisive action is needed immediately.![]()

Authors:

Toby James, Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of East Anglia

Alistair Clark, Reader in Politics, Newcastle University

Disclosure statement: Toby James' research has been externally funded by the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, British Academy, Leverhulme Trust, AHRC, ESRC, Nuffield Foundation, SSHRC and the McDougall Trust.

Alistair Clark's research has been funded by the ESRC, British Academy, the Leverhulme Trust, and the Nuffield Foundation

It Happened in America

Can our democracy survive if most Republicans think the government is illegitimate?

America faces a legitimacy crisis. Some 60 million Republicans deny Joe Biden’s victory. In an Economist-YouGov poll two weeks ago, 78 percent of President Trump’s voters claimed that the presidential election was unfair, 75 percent believed that the transition process should not begin, and 79 percent said Trump should not concede. The president welcomes this belief and pressures local officials to reverse the outcome. Congressional Republicans support him. Parts of the country are filled with “Stop the steal” protests. Rush Limbaugh talks about secession. Will Republicans ever believe that the Biden administration rightfully holds power?

Perhaps these disputes can be regarded as a minor technical delay, generating a temporary dip in public faith in the integrity of American elections that will quickly be forgotten. After all, the courts held the line. Republican local and state officials refused to break the law. The mainstream press highlighted false claims. If Biden helps vanquish the pandemic, revitalize the economy and restore a sense of normality to public life, the “sore loser effect” — observed in many contests, especially in majoritarian winner-take-all elections — may fade. Already, liberal nightmares about soft coups and widespread post-election violence from armed right-wing groups, with the victor decided by the Supreme Court, seem to have underestimated the resilience of American democracy and rule of law. And the electorate has overcome contested outcomes before: Democrats saw a travesty in Florida in 2000; some also believed that John Kerry won Ohio in 2004; the birther conspiracy held that Barack Obama was ineligible; and many Democrats argued that Trump won in 2016 thanks to intervention from Russia. None of those claims appears to have sapped the essential faith in the legitimacy of American government.

But long-term evidence indicates three reasons why this crisis may be different — and why it may worsen. If it does, it will threaten democratic governance in America.

First, in a winner-take-all presidential system, Americans are increasingly subject to minority rule. Since 1992, with a single exception (in 2004), no Republican presidential candidate has won a majority of the popular vote. Trump is a remarkable figure in American politics, but he got just 46.1 percent of the popular vote in 2016 and 46.8 percent last month, strikingly similar to John McCain’s and Mitt Romney’s totals. Nevertheless, since 1992, Republicans have occupied the White House for 12 years and run the Senate for 18 years, thanks to rules that guarantee rural overrepresentation.

Second, as Republican flag-bearers failed, the party seemed to have gradually lost confidence that it could win a majority of the popular vote in free and fair contests. There is growing evidence that adherence to soft democratic norms (not threatening critics with “Lock ’em up” or violence, for instance) crumbled, and authoritarian values and practices started to take root in the party, even before Trump descended his golden escalator. These rely on the notion that one tribe is under existential threat from another, justifying progressively more radical actions in (what adherents see as) self-defense. Republicans have sought political advantage, for instance, by suppressing voting rights through strict state voter-ID laws and limited access to convenient balloting.

After Trump took office, these tendencies worsened. Party members defended the separation of migrant parents from their children, tolerated extreme white-supremacist movements (like the one that showed up to the Charlottesville rally) and backed efforts to quash peaceful protest (as in Lafayette Square). GOP attorneys general in 18 states are now backing Trump’s push to overturn the electoral college result. Such practices will eventually become institutionalized if they become entrenched by formal laws or informal social norms.

Two recent independent cross-national studies, by the V-Dem project and the Global Party Survey, which I direct, estimate that, compared with many other political parties in the West, the position of the GOP today toward principles of liberal democracy is relatively extreme, closer to authoritarian populists such as Spain’s Vox, the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom and the Alterative for Germany, rather than mainstream conservative and center-right parties. By contrast, the Democrats are estimated to be more similar to many moderate parties within the mainstream center-left.

Finally, contentious elections in divided countries suggest that the damage here is likely to endure. The World Values Survey has monitored public attitudes toward electoral integrity across a wide range of societies since 2012. The evidence demonstrates that public faith in electoral integrity matters for feelings of political legitimacy among supporters of all parties. In general, conspiratorial beliefs about electoral fraud, rigged contests and stolen votes usually have damaging consequences. In many countries, contentious elections erode confidence in electoral authorities and procedures, deepen dissatisfaction with how democracy works, reduce citizens’ willingness to obey the law and to vote, fuel protest movements, and even, in the worst-case scenarios, trigger violence and exacerbe conflict in deeply divided societies such as such as Kenya, Belarus and Venezuela.

These risks are unlikely to undermine American democracy overnight; several resilient institutions (courts, for instance) have blocked Trump’s authoritarian pressures. But the foundations of American civic culture have been gradually weakening for decades. The World Values Survey asks whether people approve of various types of political systems, including “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections.” In 1995, 24 percent of Americans thought this was a very or fairly good idea. The figure has risen steadily, and by 2017, 38 percent approved.

In short, elections are the heart of liberal democracy. Losers voluntarily leave office. Winners assume rightful power. There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution mandating that presidents concede graciously, but it is a centuries-old practice. When faith in these fundamental norms of democracy fades, when comity between opponents erodes, so does our civic culture.

In a liberal democracy, legitimacy is the mechanism that ensures voluntary compliance with the decisions of officeholders and acceptance of the rules of the game. It’s a judgment by Americans that those in government exercise rightful legal authority. Only then are taxes paid, regulations followed and laws obeyed.

Without legitimacy, liberal democracies grind to a halt. It’s like trying to play ball without accepting a shared rule book and umpire. Liberal democracies thrive when citizens, parties and leaders battle passionately for diverse interests and ideas — they argue and debate and defend their values. But, ultimately, they also accept temporary defeats, even when they disagree ideologically with the victors. Americans will steadily lose faith in the rules of the electoral game if it turns out that players see only a zero-sum contest in which opponents cheat. Where will we be then?

The original publication is available in the Washington Post here.

THE 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS AND THE COLLAPSE OF VENEZUELAN DEMOCRACY

José Ignacio Hernández G explains how the 2020 Venezuelan parliamentary election is the least competitive election since the country recovered democracy back in 1958. The outcome is a contested election that, rather than contribute to a transition, can aggravate Venezuela's collapse and the complex humanitarian emergency that is triggering the second-worst migration crisis of the world.

Venezuela’s two presidents: evidence for choosing sides

Miguel Angel Lara Otaola

Miguel Otaola is Head of Office (Mexico and Central America) for the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA). He has a PhD in Political Science from the University of Sussex in the UK.

As demonstrated in a previous EIP blog on the May 2018 presidential contest in Venezuela, published by José Ignacio Hernández G on 30 May 2018, the election showed clear evidence of being rigged.

On 10 January 2019 Nicolas Maduro was sworn in for a second term as president of Venezuela. He obtained 67.7% of the vote in the May 2018 elections. Maduro hailed the electoral process as impeccable and claimed elections were constitutional and legitimate. For him and his supporters, democracy had triumphed. In parallel, both opposition candidates argued the process was marred with irregularities and denounced elections as undemocratic, rejecting its results. Others shared this view. The Organization of American States, for instance, called the election the ‘biggest election fraud in Latin America’.

On 23 January 2019, only two weeks after Maduro’s swearing in ceremony, Juan Guaidó, president of Venezuela’s National Assembly, proclaimed himself interim president and called for free and fair elections to restore democracy. US president Donald Trump officially recognized Guaidó – and not Maduro – as the country’s president. Similarly, a majority of American countries including Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Chile, Costa Rica and Peru called Maduro a dictator and supported Guaidó. A second group of countries - Bolivia, China, Cuba, Russia and Turkey - recognized Maduro and argued that Venezuela’s right to self-determination was under attack. Maduro dubbed this a ‘return to the 20th century of gringo interventions and coups d’état’

One position, two presidents

Two presidents. One elected as president in a controversial election, the other formally president of the National Assembly. One talking of foreign intervention to undermine him, the other calling for the organization of a free vote to determine the rightful winner. Both claiming to defend the will of the people and democracy itself. Both cannot be right. History shows many atrocities have been committed in the name of democracy. After all, North Korea is a Democratic People’s Republic and East Germany was officially known as the Deutsche Demokratische Republic. In practice, of course, both regimes were far from this ideal.

So who is making the more legitimate claim? The underlying issue is the way that the 2018 elections were conducted. More specifically, were they legitimate or not? Was this vote free and fair? To answer this we have to look at a) the context where the vote is organized and b) the integrity of the vote itself. To answer this I draw on my own research on electoral integrity in the Americas as well as leading indices on the quality of democracy and elections, by International IDEA and the Electoral Integrity Project. Only hard evidence can provide an answer.

Measuring Freedom and Fairness

First, the context. International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices are based on a broad definition of democracy and therefore not only evaluate whether a country holds ‘free and fair’ elections. They also consider other key aspects such as the extent to which access to political power is competitive, respect for fundamental rights, the extent that government power can be checked by the judiciary, parliament and the media and an impartial administration.

The indices use a 0.0 to 1.0 scale to illustrate fulfillment of each of its components. Looking at Venezuela, there has been a steady decline in all components since 1998 – the year Hugo Chavez was first elected into office. In this period, representative government, fundamental rights, checks on government and impartial administration have declined significantly. This translates into an increasing centralization of power in the executive, attacks on the opposition, control of the media and an encroachment upon key institutions namely the Judiciary and Congress. Constant attacks on the National Assembly and the staffing of tribunals with loyalists are clear examples. Figure 1 illustrates the decline in the attribute representative government (which considers aspects such as having an elected government and free political parties), going from 0.71 in 1998 to 0.33 in 2017. While Latin America experienced the ‘Third Wave’ of democracy, Venezuela clearly went in the opposite direction.

Figure 1. Representative Government, Latin America and Venezuela. 1975 – 2018.

From bad to worse

In this context, it is hard to organize a free and fair election. Nonetheless, to analyse this I rely on the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) Index. This index draws on a survey completed by experts which are asked about the quality of elections on eleven sub-dimensions including electoral laws, electoral boundaries, voter registration, campaign media, vote count and electoral authorities. Since 2012, 5,534 experts have provided information on 312 elections held in 166 countries around the world. The overall Electoral Integrity score ranges from 0 to 100.

As outlined in my research, Venezuela’s PEI index has steadily declined, going from a score of 54 for the 2012 election, to 39 in the 2013 election. The 2018 process where Maduro was elected scored 27 points. As a result, the latest PEI release (Version 6.5) places Venezuela at the lowest end of the electoral integrity scale for 2018. Its closest competitors are Iraq (with a score of 32), Malaysia (33) and Djibouti (34).

Looking at individual attributes, Venezuela’s 2018 election also performs poorly. ‘Electoral laws’ scores a dismal 12 with evidence of bias in favour of the governing party and unfairness towards smaller parties. ‘Electoral authorities’ gets 19 points, revealing a National Electoral Council (CNE) which does not act impartially. ‘Electoral procedures’, the logistical backbone of a free election, scores 16. The list goes on: the rest of the indicators are equally low and Venezuela scores significantly lower than the regional average in all of them (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Venezuela’s 2018 presidential election. Performance vs regional average.

Guaidó’s (much) stronger case

In short, the May 2018 Venezuelan presidential election fell short of international standards for conducting free and fair elections. Not only was the integrity of the election extremely low, but their legitimacy was further affected by the banning of popular opposition candidates, such as Henrique Capriles and Leopoldo Lopez. Moreover, key developments such as the dissolution of the National Assembly in 2017 and the repression of civilians by security forces during the 2017 protests make one thing clear: It is Guaidó, a democratic leader who is calling for internationally supervised free and fair elections, and not Maduro, a dictator who barely keeps a democratic façade, who should be regarded and recognized as Venezuela’s president. In that regard, the evidence is crystal clear.

Rigged Elections: Venezuela's Failed Presidential Election

The Venezuelan Presidential election was held on May 20, 2018. According to the results announced by the electoral authority (the National Electoral Council), approximately six million voters decided to reelect Maduro, with a turnout of 46%, the lowest in the Venezuelan democratic history.

Democracy and Inclusion: Expanding Ecuador’s voting accessibility

The act of voting is the most common example associated with democracy. In fact, some might argue this is the purest form of democracy, symbolizing true equality. Everyone –regardless of their ethnicity, religion or wealth – has the right to elect his or her representative. The ‘one person, one vote’ requirement translates into the ‘all men and women are created equal’ principle. For this to become a reality, everyone entitled to vote should have the possibility to do so. In practice, however, many citizens around the world are disenfranchised and myriad legal, social and even physical obstacles hamper the political participation of individuals and groups.

Flaws in Ireland’s elections

The core of Irish elections is strong, but more could be done to bring contests into the 21st Century. In particular:

Postal voting reforms would allow more people to vote early at city and county council offices.

A sustained and continuous campaign of civic information would deepen citizen’s awareness of the ballot choices.

The voter registration processes need urgent attention to address inaccuracies.

And finally a permanent Electoral Commission would strengthen administrative processes.

Why corruption and coercion flourish in flawed elections

Electoral malpractice – from subtle disinformation campaigns through to bribery, corruption and overt physical intimidation – undermine democratic contests across the world. A new report by Pippa Norris, Thomas Wynter and Sarah Cameron from the Electoral Integrity Project, which adds 44 election evaluations from 2017 to its rolling survey of elections, finds that electoral corruption and coercion are related to one another, and more prevalent in societies that are poorer, less democratic, and heavily dependent on natural resources.

Transitioning from War to Peace: The Dilemmas of Transitional Elections

The transition from war to peace is a long and often complicated process involving a number of components that range from the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of former combatants to agreements on the form and structure that national (and local) governments will take after the conflict.

Making voting both simple and secure is a challenge for democracies

Recent elections around the world have raised concerns about the procedures used for voter registration and their potential consequences. This article by Norris, Cameron and Wynter presents the results of the EIP Perceptions of Electoral Integrity survey evidence concerning the quality of these procedures in 161 countries that held 260 national elections from January 1 to June 30, 2017. The study concludes that it’s critical to strike the right trade-off between making registration accessible and making it secure.

Trump’s Global Democracy Retreat

Why the younger generation of Corbysandistas?

Across the pond, one of the most remarkable developments in recent elections has been the propensity for younger citizens not only to vote – and also to cast ballots in massive numbers in support of older socialist leaders advocating left-wing economic policies last fashionable during the 1970s. What explains this?

Populism, RIP?

Is the rising time of populism stalled? It is apparent that headline reports joyfully proclaiming the death of populism are premature. The results in a series of recent European elections suggest that voting support for this phenomenon is growing, due to a cultural backlash, even if leaders fail to win office, and support is unlikely to diminish as a long-term trend.